Communicating is Not Storytelling is Not Writing

What IS writing?

I spent 15 years writing for a living before I decided to write for myself. In this decade and a half, I fit my dreams of being a writer into places where I would also receive a paycheck. That led me to professional communications, mostly for nonprofits, and where I’d write newsletters, blogs and the daily Tweet or two, back when retweeting was a manual endeavor and the 140 character limit was sacrosanct.

I would like to think I was a good writer when I started my career, but I probably wasn’t. It took me years to hone my professional craft to be able to write, for example, a compelling, concise op-ed that would engage a reader through evocative prose and clear examples. I learned how to outline a piece, how to make the writing flow from one paragraph to another, and most importantly, identify an idea that would rise to the top of the content muck that is the internet. Because I was almost never writing in my own voice, but the voice of my boss or CEO, I learned how to translate the ideas of others—which were usually scattered and not consistent—into something that another person would want to read.

After going through some life changes—little things, like having children and starting my own ghostwriting business—I took a look around at where I found myself and saw something was missing. Despite filling my days with writing, none of it was my own.

I began to write creatively, figuring that what I had learned as a communications professional would easily translate into short stories and maybe even a novel. Whoops! Nope.

What I had learned as effective communication—delivering clear, poignant and emotional prose that moves a reader to do something—was not necessarily good writing, as I was trying to produce in my stories. I found myself leaning heavily on exposition to explain situations and give context, with characters that did not necessarily jump off the page. Some of this was due to my rookie status as a creative writer, sure, but also because I was conflating one kind of writing with another.

Communication is not the same as writing, in the same way that singing is not the same as talking. Both use vocal modulations, but they require completely different skill sets and have different aims. To use a reductive example: Dr. King was excellent at talking—maybe the best? – but I do not believe he was a skilled singer. He—and other great orators—have a rich craft to deliver a compelling speech that includes leveraging their voice as an instrument, but an instrument distinct from any musicality.

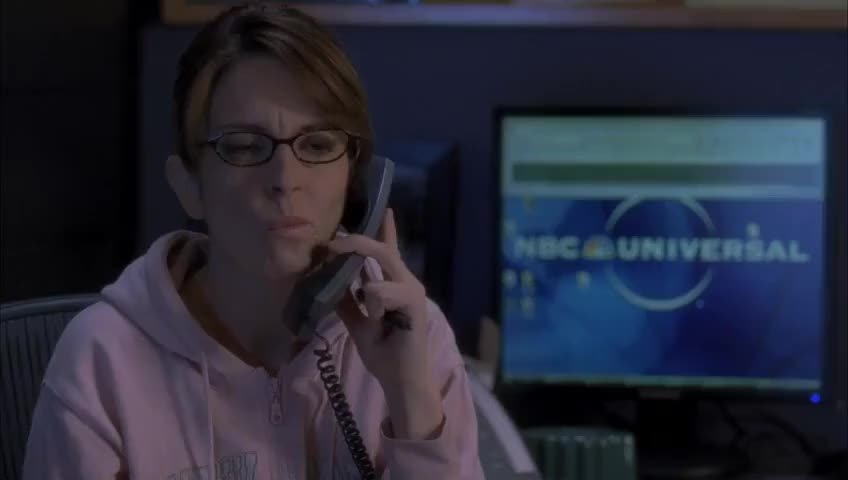

Similarly, when people refer to “writing” with creative aims, they are usually referring to something more akin to “storytelling.” “Writing” is a vague term that can have so many meanings. I’ve found myself, at times, staring at the words on my screen, not quite doing what I want them to do, and asking myself, “what IS writing?” like a baffled Liz Lemon when presented with predilections of business school. I assume that assembling words on a page (screen) for the delivery of information was materially the same as assembling words on a page (screen) for the delivery of a made-up story, sprung from nowhere but my own mind. But turns out, it’s about as similar as reciting the “I Have a Dream Speech” is to singing an opera.

As I read more about writing of the creative type, and talk with others about the process, and take classes to improve my craft, I find that so much of the conversation is not at all about how to put one word in front of the other in the most effective way, but instead the nature of the characters being constructed and the plot lines unfolding. It becomes less about what I thought I was getting into—writing words—and more about what is behind those words. A character or place or scene can be beautifully described, with the most compelling or lavish language, but if those elements are not well conceived, then, well, what’s the point? (This type of writing, at its worst, can be writing “that calls attention to itself,” as Richard Russo pointed out.)

Deconstructing what makes communicating and storytelling different from each other (even if they end up in the same place of “words on a page,”) has helped me see their similar core. By removing the writing from both, and focusing on the essential components, we find that what remains is the same: Ideas. Characters in a story are not real – as much as writers say that they let the stories guide them and the characters speak to them. I’ve found this to be true in my own creative writing, but ultimately, all elements in a story are all things made up to evoke some reaction in the reader. They are, basically, ideas put into a storytelling form.

The (creative) author wants to achieve something with their piece, whether it’s an exploration of a few characters, some kind of commentary on society, or building a fun world, or telling a gripping narrative, or just making the reader feel something. All elements of the story are assembled with that aim in mind. Some of those elements and ideas emerge during the writing, creating what Robert Boswell calls “narrative spandrels.” Boswell compares the little, unplanned details that end up making a story beautiful, that tie it all together, to the decorative by-products of the arches in a cathedral. (Which can completely derail or re-write a story, if the author so desires.)

Writing for the purpose of conveying prescriptive information has a similar construction to a story cathedral. First, the author determines her goals. Ideas are considered, rejected, assembled into components, and built up to be delivered in an effective and evocative manner. Examples are used to illustrate a point, develop emotions, all in the hopes that the reader will learn something or do something (call your Congressperson; buy my product; like and subscribe). Storytelling does have its place in prescriptive nonfiction, of course, because without real world examples, any nonfiction book would essentially be a textbook. But this act of storytelling is one element of a broader toolkit of assembling ideas to meet whatever goals the author wants to achieve.

I don’t know if this breakdown of the distinction between different types of writing is helpful to anyone else, but I found the stripping out of the writing from the process a freeing exercise. It made both communicating and storytelling less intimidating. There was a certain freedom in seeing the components from the whole, and understanding that, like anything else, good writing, in whatever form, is built one element at a time.

I refined my craft as a communicator doing the only thing I knew how: by writing. I wrote and edited probably thousands of pieces in that muddy category of “thought leadership”: blog posts, articles, newsletters, op-eds. I still do this, and I still enjoy it, but I see it as different and almost completely separate from the kind of writing I do creatively. As I move on to the challenge of refining my creative writing craft, I’ll do so the only way I know how: by writing.

This piece was originally published on Angry Gable Press.